Puyal & Peret

In the 80s and 90s there wasn't a lot of up to date Spanish news in England. The news that filtered through was usually two or three days old by the time the latest edition of El Pais made it to the kiosks of central London. My relatives would sometimes come over to England to visit and then spend hours walking around Kensington in search of a copy of La Vanguardia.

It was a reflection of just how little Spanish or wider European news registered with the British public. News coverage on the BBC rarely extended beyond the latest ETA attack or diplomatic row over Gibraltar. Very occasionally, Catalonia would get a mention, eg when Barcelona won the Olympic bid or when the Catalan government led by Jordi Pujol took out a two page ad in The Sunday Times to inform readers that Catalonia was a 'nation within a nation'. For those after real time news, their best bet was the radio.

Spanish broadcasters are exceptionally good at radio. It's a language that lends itself well to flowing commentary, debate, expression, celebration. My first conscious exposure to Spanish radio however wasn't in Spain at all but in London in my early teens. Whilst never a football fan as a kid I was intrigued by Barça the footballing behemoth and had followed the anglicisation of its ranks via Venables, Lineker et al. A show came to my attention called Radiogaceta de los deportes which went out on Radio Exterior de España on Sundays when most of the league fixtures were played.

Spanish football coverage felt incredibly exciting compared to England. Far from tiresome old pros mumbling clichés though all the awkward pregnant pauses, these commentators were energised, passionate and unashamedly partisan, elevating coverage of the game to an artform. On shortwave you were often straining to hear what was said beneath the cacophony of crackling and intermittent interference from other networks. With my limited Spanish it was an even bigger challenge, but I soon learnt the basics: saque de esquina, remate, tarjeta, fuera de juego, entrada durísima.. whilst the euphoric moments were more immediately understood.

Back in Barcelona, around the same time of evening, my gran would be tuning into Catalunya Radio for their Liga coverage, which was hosted by legendary commentator Joaquim Maria Puyal, arguably the most excitable sports journalist in the history of the game, a man so passionate about Barça you couldn't help but worry about his heart. It was the iconic, almost operatic voice of Puyal which carried Barça fans through some of the club's most famous celebrations, the European Cup win at Wembley in 1992 or the closing day of the season when Tenerife famously denied Real Madrid the title. Combined with the Catalan absorbed watching TV3, I think I learnt more vocab via football than in any language class.

During holiday visits to Barcelona I would often retreat to the spare room where my gran had one of those boxlike plastic Phillips turntable/twin cassette deck units with the elaborate graphic equalisers that didn't do anything. Scrambling along the dial you would stumble across all these FM stations which seemed - but in retrospect probably weren’t - very different from British ones. I noticed the way people would be cut off by the pips midflow, which was less amusing when you were taping music at the time. The nearest equivalent to the BBC was state broadcaster RNE Radio Nacional de España or Cadena SER. The biggest private one was COPE, hated by my family for all sorts of political and religious reasons which marked them out as the enemy.

Then there were the music stations in between. The pure planet pop of Los 40 Principales or the disco-funky of Radio Club 25. The one which stood out for me was a station called Radio Tiempo which seemed to come alive in the evenings. One of Barcelona's best known radio presenters, Toni Peret seemed to be on there every night, hosting a show called It's Your Time. He was the Catalan Pete Tong in many ways, playing a bit of everything with a populist appeal. Hugely influential, and later credited - for better or worse - with bringing reggaeton to the mainstream, this was a man with an instantly recognisable voice, custom-designed for radio, with seemingly instant access to every 12 inch on the market.

This was an era when it was not uncommon to hear crude Ben Liebrand inspired megamixes of all the big hits, turbo charged bangers featuring helium vocals, didgeridoos, panpipes, gregorian chants, church bells, syncopated orgasms, sampled cockerells, bagpipes, gunshots, Saddam Hussein warchants, cult Tarantino dialogue and pseudo-philosophical mantras on tracks (in the case of B-Tribe - previously discussed HERE - on the same track). ‘No Go’ areas did not exist in the quest for novelty hits, with ever more questionable taste, longevity or quality control.

For a puzzled teen sat there trying to understand the radio in a foreign country it was all strangely fascinating. Nobody in style and ‘attitude’ conscious London would ever touch this stuff and, of course, on any creative, artistic level it was the very essence of trash; but the energy seemed to connect with a Spanish yoof that didn't didn't take this stuff too seriously. And for a while, immersed in the show, neither did I.

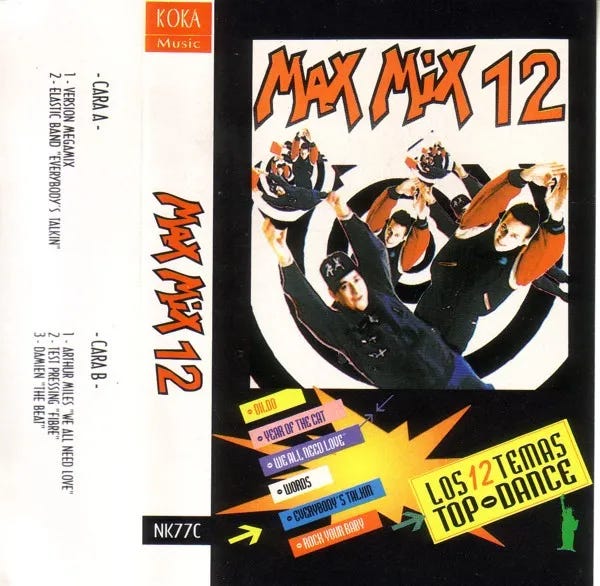

Toni Peret became a local institution in Barcelona. Emerging DJs such as Quique Tejada and José Maria Castells often appeared beside him on the show. Together they called themselves The Dream Team, probably after the US Olympic basketball team or Johan Cruyff's title winners. If this all sounds absurd, the hard numbers were anything but. The Spanish commercial dance market was worth big bucks, churning out cheaply assembled seasonal compilation CDs with names such as Max Mix, Bolero Mix and Lo Más Duro, which sold by the hundreds of thousands, an industry model lucrative enough to draw the attention of some unsavoury figures.

On the afternoon of September 3, 1998 Castells was kidnapped in Barcelona by three Mexican gangsters. He was abducted, beaten, and gagged before being dumped by the La Baells reservoir, on the outskirts of Berga 110km north of the city. During the assault his assailants also stole a Rolex watch and gold rings, a mobile phone and 160,000 pesetas in cash, acting on the orders of a major player in the Spanish record industry, Miguel Degá, a record executive at the Mix Max label with a vendetta against his business associate Ricardo Campoy.

Unfortunately for the Mexicans, they got the WRONG man, confusing Campoy with Castells! The news sent shockwaves around Barcelona and the villains all received jail terms and fines. In further twists to the story, Degá later escaped from jail whilst his son was murdered outside a disco. It all felt so far removed from the innocence and amateurishness of those radio shows five years earlier. This is a good read for anyone interested in the darker mafia practices of the 90s dance megamix industry.

Since then I’ve noticed huge changes to Spanish radio as it entered the digital age. By any quantitative - if not qualitative - measure, there is more choice than ever, though of course, the devil is in the detail. The leftfield is barely represented on FM although there are shows on RNE3 and RNE4 and Catalunya Radio such as Miqui Puig's Pista de fusta show which still tap into the underground.

In an era of niche streaming though, what place does FM radio have now for music fans? The advent of audiovisual radio interviews also means the juiciest soundbites or gaffes are all over social media in an instant. You hardly need to tune in to them when they tune into you.

In recent years I even appeared on the radio myself. In perhaps the only instance of nepotism in my life - or what is known locally as an enchufe - a family friend set me up with an interview for a job at Catalunya Radio to discuss a possible segment on Catalan players in the Premier League - only for them to cool on the idea. I did however appear on a few things after relocating to Barcelona, sometimes in strange circumstances.

At the height of all the Catalan independence drama some researcher at The Huffington Post read my tweets and bizarrely contacted me for interview, convinced I was an authority on the topic. I’ll never know if anyone in the USA heard me bluffing my way through but it did make me wonder - with some alarm - what other halfwits get wheeled out for their insight.

There was also a panel appearance on Barcelona City FM with ERC separatist Jordi Vilanova and a British expat called Simon Harris (later unmasked as a far right extremist, who died during lockdown). I think those farcical situations led me to get out of online politics and stick to other things eg discussing music on specialist programming like DubLab, one of the best stations in the business.

Whether sport, music or news, Spanish radio has been a constant throughout my adult life. Whether it will continue to entice younger listeners is another matter, but it certainly helped me better understand this country.

*For anyone wanting to learn more about the history of Spanish radio, I urge you to contact my good friend David Puente who has given lectures on the topic and would be only too happy to share his knowledge.